Hawaii's False Alarm Leads to Changes in Emergency Communication Systems

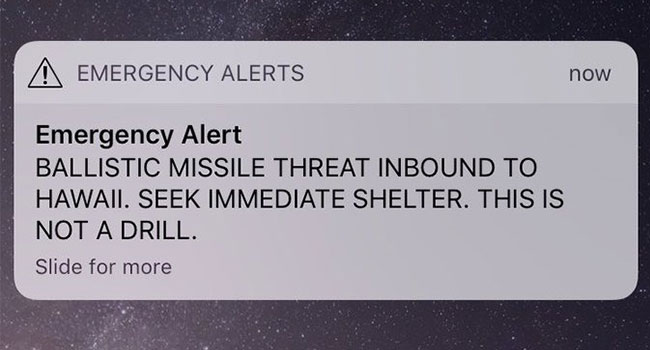

On Saturday, people in Hawaii received an emergency notification warning of an imminent nuclear missile attack.

- By Sydny Shepard

- Jan 17, 2018

For nearly an entire hour on Saturday, the people of Hawaii prepared for the worst. Parents called their children, students ran for the nearest underground shelter and families hid in their bathtubs and basements after receiving an emergency notification from the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency (HEMA) that a "ballistic missile threat" was inbound to the state.

Thirty-eight minutes later, they received another notification. This time, the message informed Hawaiians that the missile threat was a "false alarm."

In the hours after the false alarm notification, HEMA explained the whole ordeal was a simple mistake made by an employee during a shift change.

On Sunday, Federal Communications Commissions Chairman Ajit Pai called the false alert, "absolutely unacceptable" and said a full investigation was "well underway."

"Based on the information we have collected so far, it appears that the government of Hawaii did not have reasonable safeguards or process controls in place to prevent the transmission of a false alert," Pai said in a statement. "Federal, state and local officials throughout the country need to work together to identify any vulnerabilities to false alerts and do what's necessary to fix them. We also must ensure that corrections are issued immediately in the event that a false alarm goes out."

Wireless emergency alerts are typically dispatched during emergency situations - to warn the public of dangerous weather, missing children, and security threats - and are a partnership of the FCC, FEMA and the wireless industry. While the FCC establishes rules and regulations surrounding emergency alerting, responsibility for sending those messages typically falls to emergency management officials, according to The Washington Post.

The situation on Saturday was worsened when Hawaii officials realized that there was no system in place at the state emergency agency for correcting the error. The state agency had standing permission through FEMA to use civil warning systems to send out the missile alert, but not to send out a subsequent false alarm notification.

"We had to double back and work with FEMA [to carft and approve the false alarm alert] and that's what took time," HEMA spokesperson Richard Rapoza said.

Rapoza said that has since been fixed with a cancellation option that can be triggered within seconds of the mistake.

"In the past there was no cancellation button," Rapoza said. "There was no false alarm button at all. Now there is a command to issue a message immediately that goes over on the same system saying 'It's a false alarm. Please disregard.' as soon as the mistake is identified."

The HEMA said it has also suspended all internal drills until the investigation is completed. In addition, it has put in place a "two-person activation/verification" rule for tests and actual missile launch notifications.

“Part of the problem was it was too easy — for anyone — to make such a big mistake,” Rapoza said. “We have to make sure that we’re not looking for retribution, but we should be fixing the problems in the system. . . . I know that it’s a very, very difficult situation for him.”

The employee has since been reassigned to a new position at HEMA.

About the Author

Sydny Shepard is the Executive Editor of Campus Security & Life Safety.